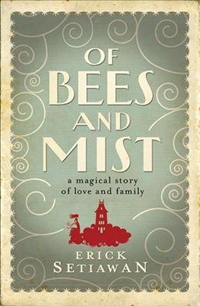

This is a trul y strange book – compulsively readable and annoying in equal measure. The cover is a bit of a giveaway consisting as it does of the title in big art deco letters on a grey background with a few white curlicues ie we’ve got no idea how to classify this. Just above the author’s name is a small picturebook-like silhouette of a tower on a cloud with a windswept woman’s figure. The publisher is tentatively suggesting this might be a kid’s fantasy.

y strange book – compulsively readable and annoying in equal measure. The cover is a bit of a giveaway consisting as it does of the title in big art deco letters on a grey background with a few white curlicues ie we’ve got no idea how to classify this. Just above the author’s name is a small picturebook-like silhouette of a tower on a cloud with a windswept woman’s figure. The publisher is tentatively suggesting this might be a kid’s fantasy.

This could be a fantasy book except it is set in a picturebook ‘real world’, in a city that might be northern European, central European or Asian; it has elements of each. It could be in medieval times, the nineteenth century or contemporary times. The clothes don’t help. In one place the heroine, Meridia, wears a knee length dress, yet her father wears a top hat and cloak. Everyone walks – there are no horses, or cars, or trains. In the gardens there are roses and marigolds but also bougainvillea, the food is cakes and sandwiches but also ginger and garlic and noodles. If we accept this hybrid world it is only one step further to accept that there are yellow and blue mists that enfold Meridia’s father when he leaves the house, that the house is perpetually freezing no matter the heat outside, and that Meridia’s mother-in-law dominates her family with vicious attacking bees that aren’t visible to others.

In Meridia’s world there are fortune tellers, invisible friends and people who fade into their spirit beings but there’s also school, romance and marriage, housekeeping and starting up a business. This mishmash of elements would be fatally off putting if it wasn’t for the strong narrative drive and the barrage of mysteries to be resolved. Meridia’s mother-in-law is a truly horrendous character, such a narcissistic sociopath that she doesn’t really need the (supernatural) bees the author bestows on her to perpetuate her horrors. Be warned, her comeuppance is a long-time coming.

The novel has been called magic realism, but it doesn’t quite fit that description, also an adult fairytale. That tag doesn’t really fit either but is closer to the mark. There are sexual references and crudity of language that mark this out as ‘adult’ whereas the story itself could be young adult, or teen. Perhaps as the phenomenon of Harry Potter showed, adults do want to read young fantasy books, and Of Bees and Mist has tapped into this. Interestingly, however, they’ve marketed the novel as general fiction, not fantasy.

I found it unsettling: I thought Meridia a little too self-satisfied, her husband a dolt, the feud between Meridia’s parents unbelievable and the fate of many characters unfair but, bloody hell, I couldn’t stop reading until I’d bolted through to the end.