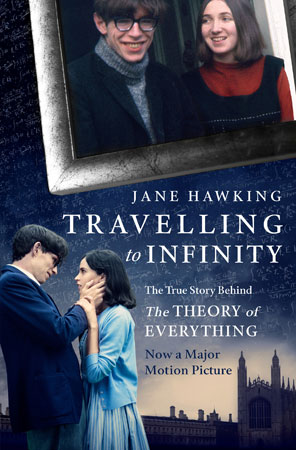

The photo on the front cover of Jane Hawking’s autobiography of her long marriage to Stephen Hawking shows a bookish long-haired Jane and a mop haired, handsome Stephen Hawking – both look cool and stylishly 60s. Yes, they did fall in love in the sixties – he a brilliant PhD student at Cambridge, she a languages student in London. The window for young love was terribly narrow as Stephen was given the motor neurone disease diagnosis in his early twenties – when he asked her to marry him he knew his prognosis, and so did she. The doctors gave him only a few years to live – they thought they should enjoy married life while they could; Jane tells us she loved him, and so of course she would marry him.

The photo on the front cover of Jane Hawking’s autobiography of her long marriage to Stephen Hawking shows a bookish long-haired Jane and a mop haired, handsome Stephen Hawking – both look cool and stylishly 60s. Yes, they did fall in love in the sixties – he a brilliant PhD student at Cambridge, she a languages student in London. The window for young love was terribly narrow as Stephen was given the motor neurone disease diagnosis in his early twenties – when he asked her to marry him he knew his prognosis, and so did she. The doctors gave him only a few years to live – they thought they should enjoy married life while they could; Jane tells us she loved him, and so of course she would marry him.

Her parents were less sanguine, and so were his, although, as it transpired they appeared to hand over responsibility for Stephen totally to Jane, and it was not long until that responsibility was particularly onerous.

One of the problems, perhaps, with this book is that it is, necessarily one sided – it’s Jane’s story. But that is the interest of it – it appears to be scrupulously honest, detailed, reflective and unflinching. We are given enough detail and context to make up our own minds.

In another writer’s hands, this account of a marriage, an astounding career, the visceral trials of disability, a family under strain and, ultimately, various degrees of betrayal, could have been prurient. But Jane goes to great lengths to show her love and dedication to Stephen, and to give credit to his work but we also see the increasing strain of it all, and how the struggling family is left to cope on their own (amazingly, it was not until very late in the piece that they got any nursing or home help at all).

On the face of it, they had an enviable life – Stephen was recognised early as a brilliant mind and he was given a number of posts at a college at Cambridge university. They lived in a heritage house in Little St Mary’s Lane close to the uni and the river, but the reality was the ‘posts’ Stephen held were paid miserably and the house was small, cramped and uncomfortable (he couldn’t teach so he didn’t go through the normal academic trajectory). Children soon came and Jane had to raise toddlers as well as assist Stephen who deteriorated quickly. Stephen insisted she go with him overseas to awards and conferences, to further his career, dragging the kids. She was privileged to go all over the world (the account of Soviet-era Russia is particularly interesting) but it was an incredible strain, and Stephen’s wishes were always paramount.

Jane makes much of how the wives were known as physics widows. Many of these women (Jane included) were qualified and intellectually gifted, but the physics always came first, and it would be beyond the pale to put your own interests before, you know, little things like: ‘the origin of the universe’, ‘black holes’ and ‘the theory of everything’. As the years wore on and Stephen became more severely disabled, he seemed to become more determined, more autocratic and demanding. Jane would be the first to say he was courageous in his suffering – before he had a tracheotomy, he had coughing fits during which he must have thought he was dying – but he appears to have utter confidence in his superiority and importance, and complete belief that Jane should devote her life to him, even above the children.

My reading is that Stephen was a complete tyrant, maybe he had to be to survive. On the positive side he loved his children, even though, and much to Jane’s bitter regret, he relied heavily on his eldest son (Robert) to help him physically, the responsibility depriving Robert of part of his childhood.

I couldn’t help but be on Jane’s side in this book. She was not a paragon of virtue but she did devote much of her young adult life, and middle age, to Stephen – she did manage to complete a PhD herself in this time but it took her over ten years to do so.

As is often the case in marriage breakups, when Stephen made a significant amount of money from the immense success of ‘A Brief History of Time’ Jane didn’t get to see the proceeds. As Stephen became more and more successful and famous, his body became more and more infirm – in the later stages of the marriage they could finally afford nurses to help look after Stephen. But for Jane this wasn’t a much-awaited respite but just more worry as the nurses squabbled, or were neglectful, or treated the family with contempt. Jane hated that the family, especially the school-aged children, had to relinquish their privacy.

The advent of the nurses also, unwittingly, brought about the end of the marriage. Stephen left the family for one of the nurses, Elaine Mason. By all accounts, Elaine appeared to idolise Stephen – she would berate Jane, accusing her of not giving up everything for Stephen, the great man. Jane, by her own account, was shell-shocked at Stephen’s request for a divorce, however, from an outsider’s viewpoint her (admittedly platonic) relationship with another man – Jonathan – over many years, must have allowed Stephen to feel he was justified in looking elsewhere. Jonathan did help the family with assisting with meals, chores, transport and physically helping Stephen but, if Jane and he were in love, it must have been obvious to everyone and humiliating for Stephen, although he never said so. Perhaps it took Elaine to point it out.

The whole Stephen/Elaine thing takes up very little space in this long book, and Jane doesn’t dwell on it. You can learn more online about the accusations of abuse and the subsequent divorce. For Jane’s part, she married Jonathan, renovated a house in France and wrote her own very successful book. Latterly, it appears that Stephen and Jane have become friends again – apparently Stephen thought the film made of their early life ‘The Theory of Everything’ was a pretty accurate account – perhaps flattered at Eddie Redmayne’s portrayal of him – that would be just like Stephen’s immense ego.