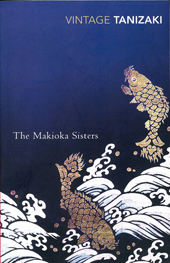

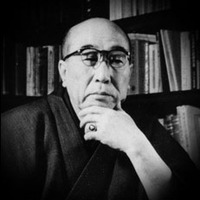

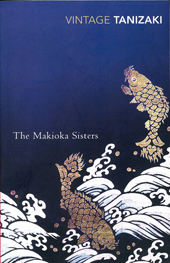

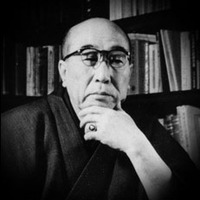

Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965) was, up until his death, regarded as Japan’s greatest contemporary author. The Makioka Sisters is his most famous novel translated into 14 languages. The English language translation by Edward Seidensticker was published in 1957.

Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965) was, up until his death, regarded as Japan’s greatest contemporary author. The Makioka Sisters is his most famous novel translated into 14 languages. The English language translation by Edward Seidensticker was published in 1957.

The Makioka Sisters (published in Japan as A Light Snowfall – 1943-48) covers five years in the lives of four sisters in pre-second world war Osaka. What struck me most about the book is its leisurely style. Although it was written in the early forties there is definitely something of the late Victorian era about it.

The story is mostly told through the point of view of Sachiko, the happily married second sister and her responses to the predicaments of her other sisters, in particular, Taeko, the youngest and most modern of the sisters and the enigmatic Yukiko.

The drama of the story resides in the ongoing attempts to find Yukiko a husband – arranged marriages still occur for well-to-do families – and in the attempts by Taeko to be independent from her family, and to choose her own husband and have control of her own life.

The trials and tribulations take place in a tightly controlled society where “the main house”, that is, the house of Sachiko’s eldest sister and her husband (who has married in to the family and is now its head) has precedence over the sisters’ lives, and who they must defer to.

The beauty of the book is the minutiae of Japanese life at a fascinating period. In some ways Japan was westernised at the time, especially in the main cities. People travelled overseas and foreigners working for Japanese firms were common.

The Makiokas’ houses have Japanese rooms and Western rooms and the women wear both kimono and Western clothes. I was under the misapprehension that Japan was a very traditional society until being westernised after the war.

I also loved the aspects of Japanese life which haven’t changed for centuries- (just read the eleventh-century The Tale of Genji – which incidentally Tanizaki translated into modern Japanese) – the love of music, dance, kabuki and poetry. A scene I particularly loved was when Sachiko, her husband, and her daughter, sit down to write haiku poetry after viewing the autumn moon from the garden. Yukiko is away and homesick in Tokyo so they roll up the poems and tie them with sheaves of autumn grass to send off to her.

I also loved the aspects of Japanese life which haven’t changed for centuries- (just read the eleventh-century The Tale of Genji – which incidentally Tanizaki translated into modern Japanese) – the love of music, dance, kabuki and poetry. A scene I particularly loved was when Sachiko, her husband, and her daughter, sit down to write haiku poetry after viewing the autumn moon from the garden. Yukiko is away and homesick in Tokyo so they roll up the poems and tie them with sheaves of autumn grass to send off to her.

The family tensions and drama are given added poignancy because we know (as the characters do not and neither did the author at the time he began to write the novel) that very soon the war will bring utter devastation to Japan that will irrevocably change their way of life.

The novel was serialised beginning in 1943, at the height of war, and it fell foul of the Japanese censors and publication was halted. The full novel, in three parts, was published after the war.

After going so far with the Makiokas, through floods, sickness, miscarriages, I found the ending abrupt and somehow unsatisfying. The fates of the sisters were not bright enough nor dramatic enough, but perhaps that’s my cultural expectation, especially as the novel takes the Victorian family saga form in which we’re used to seeing our heroines richly rewarded for their trials.

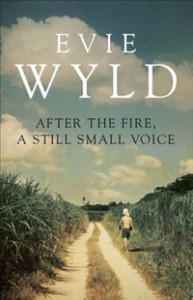

Three Australian authors have made it onto the Dublin IMPAC literary award (nominees are put forward by libraries).

Three Australian authors have made it onto the Dublin IMPAC literary award (nominees are put forward by libraries).