Apparently, Rebecca has not been out of print since it was first published in 1938. It was boosted, no doubt, by the 1940 Hitchcock film starring Joan Fontaine and Laurence Olivier, and with many adaptations since (Netflix has one in the pipeline). I first read Rebecca many years ago in my twenties and loved it. First and foremost, it is a very well written mystery. Du Maurier is excellent at misdirection, withholding and building a tense, slightly Gothic atmosphere. It’s not for nothing that the opening line ‘Last night I dreamed I went to Manderley again’ has gone into the popular imagination.

I have to admit that my second ‘reading’ was really listening to the audiobook narrated by the well-known actress, Anna Massey. Her voice is, I think, too old for the young narrator (in her early twenties) but, in defence of Massey, the novel is narrated in retrospect by the older ‘never mind how many years’ unnamed narrator. I will call her J, for Jane, as the parallels to Jane Eyre are obvious, and we can’t keep mixing her up with the first Mrs De W. Massey adopts a posh, upper class intonation that, initially, is very annoying. However, it is also appropriate – Maxim de Winter is stinking rich. Manderley is a huge stately home with a large number of servants, including the butler, Frith and, of course, Mrs Danvers the housekeeper. She is no char, she runs the large staff, providing Mrs de Winter with a menu in the morning for the day’s meals. It is one of the first instances of her distain for the new Mrs de Winter, that she has no opinion on this. ‘Whatever you think, Mrs Danvers’ is her perpetual reply. Maxim has an estate manager, Frank Crawley, and so doesn’t have to do any very much by the way of oversight. We first meet Maxim, as does J, in a fancy hotel in Monte Carlo where J is suffering the petty humiliations of being a companion to the wealthy American Mrs Van Hopper.

Coming to this book the second time around, there were things that irritated me quite a lot. One aspect was the leisured lifestyle of de Winter. Somehow, because Manderley is so beloved by Maxim, that makes the idea of his immense wealth acceptable. Because of J’s meekness and mildness, there is no suggestion she is desirous of this wealth. In fact, her main concern is not being up to the job of lady of the house. Her, tastes, we are led to believe, are modest and simple: she has shabby clothes that she doesn’t appear to update when she arrives at Manderley, ‘I can see myself now … with straight, bobbed hair and youthful unpowdered face, dressed in an ill-fitting coat and skirt and a jumper of my own creation.’ No wonder Mrs Danvers looks on with cold disapproval. Du Maurier cleverly deflects any criticism of J and Maxim by presenting them first to the reader in their exile in Europe: for reasons unknown to us until late in the narrative, they can’t return to their beloved Manderley and are instead made to live a quiet life in small hotels awaiting their the English papers and their tea (No, don’t be silly, they can’t find something useful to do. Poor old Maxim is born into the idle rich. No, they can’t take an interest in the countries they are in. It’s not England. The light is too bright and hurts J’s eyes!) Their exile is obviously painful, (and we want to find out why) so we forgive them their xenophobia.

Coming to this book the second time around, there were things that irritated me quite a lot. One aspect was the leisured lifestyle of de Winter. Somehow, because Manderley is so beloved by Maxim, that makes the idea of his immense wealth acceptable. Because of J’s meekness and mildness, there is no suggestion she is desirous of this wealth. In fact, her main concern is not being up to the job of lady of the house. Her, tastes, we are led to believe, are modest and simple: she has shabby clothes that she doesn’t appear to update when she arrives at Manderley, ‘I can see myself now … with straight, bobbed hair and youthful unpowdered face, dressed in an ill-fitting coat and skirt and a jumper of my own creation.’ No wonder Mrs Danvers looks on with cold disapproval. Du Maurier cleverly deflects any criticism of J and Maxim by presenting them first to the reader in their exile in Europe: for reasons unknown to us until late in the narrative, they can’t return to their beloved Manderley and are instead made to live a quiet life in small hotels awaiting their the English papers and their tea (No, don’t be silly, they can’t find something useful to do. Poor old Maxim is born into the idle rich. No, they can’t take an interest in the countries they are in. It’s not England. The light is too bright and hurts J’s eyes!) Their exile is obviously painful, (and we want to find out why) so we forgive them their xenophobia.

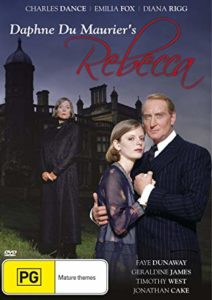

Then, of course, J is a nobody. She is well-bred and middle class, and has finer feelings, because she cringes at the overbearing antics of Mrs van Hopper. We first meet Maxim when he lunches at the next table in the hotel. Old Hopper pounces on him and, of course, he has to put up with her because she’s wealthy and upper-class New York. Luckily, the old termagant gets a cold and Maxim can whisk J around in his car. Here is the romance trope – wealthy, distant, confident man falls for poor (usually beautiful) but good and sensitive girl. The ordinary woman reader puts herself in place of the girl (if only, she fantasises). Like Jane Eyre, J is not beautiful but ‘plain’, although we suspect the plainness is really a lack of confidence (it is interesting in film/TV adaptations the actresses are not ‘plain’). Of course, thinks the heroine, this rich, confident man couldn’t love me, and from this comes the trials and the tribulations of our Janes.

Then, of course, J is a nobody. She is well-bred and middle class, and has finer feelings, because she cringes at the overbearing antics of Mrs van Hopper. We first meet Maxim when he lunches at the next table in the hotel. Old Hopper pounces on him and, of course, he has to put up with her because she’s wealthy and upper-class New York. Luckily, the old termagant gets a cold and Maxim can whisk J around in his car. Here is the romance trope – wealthy, distant, confident man falls for poor (usually beautiful) but good and sensitive girl. The ordinary woman reader puts herself in place of the girl (if only, she fantasises). Like Jane Eyre, J is not beautiful but ‘plain’, although we suspect the plainness is really a lack of confidence (it is interesting in film/TV adaptations the actresses are not ‘plain’). Of course, thinks the heroine, this rich, confident man couldn’t love me, and from this comes the trials and the tribulations of our Janes.

This brings me to my next gripe. I couldn’t stand J’s diffidence in the face of Mrs Danvers and the county types she has to deal with at Manderley. J is forever hiding behind doors so as not to be seen, breaking expensive ornaments and hiding them, scuttling upstairs when visitors come … Perhaps as a younger reader I could relate to this but now I wanted to scream at J. When Danvers catches J in Rebecca’s old room, J acts like she’s a child caught out, she’s terrified and rooted to the spot while Danvers goes around showing her all Rebecca’s beautiful things – even the nightdress she wore before she died still crinkled with use (icky, but nice touch Daphne!). Yes, I know, du Maurier has to work it so that J is intimidated and jealous of Rebecca so that she can set up the betrayal scene at the ball, but does J have to be that wet?

This brings me to my next gripe. I couldn’t stand J’s diffidence in the face of Mrs Danvers and the county types she has to deal with at Manderley. J is forever hiding behind doors so as not to be seen, breaking expensive ornaments and hiding them, scuttling upstairs when visitors come … Perhaps as a younger reader I could relate to this but now I wanted to scream at J. When Danvers catches J in Rebecca’s old room, J acts like she’s a child caught out, she’s terrified and rooted to the spot while Danvers goes around showing her all Rebecca’s beautiful things – even the nightdress she wore before she died still crinkled with use (icky, but nice touch Daphne!). Yes, I know, du Maurier has to work it so that J is intimidated and jealous of Rebecca so that she can set up the betrayal scene at the ball, but does J have to be that wet?

I also took objection to J’s continual deference to Maxim – yes dear, no dear, of course dear. Somehow in this romance trope, it doesn’t matter what the man is like – that his character, at least on the surface is obnoxious – he has to be distant, brusque, self-confident so that the ‘winning’ of him is all the sweeter. Maxim is pretty much a self-centred arrogant toff. He doesn’t really share things with J, but plonks her down in Manderley and expects her to work things out for herself. He infantilises her but at least she is aware of this and it begins to grate on her. Why he should choose her for his attentions in Monte Carlo is not made clear. The reader hopes it is because he sees that J is fundamentally decent and kind and is in need of rescue from the horrible Hopper. Like Rochester in Jane Eyre his feeling have to necessarily be opaque (they are both hiding secrets) so that the heroine can misconstrue them. However, as the story progresses, we can see that he needed someone compliant, who would love him without making demands of her own, she would lack her own agency, so much so that she would forgive him his transgression. As in Jane Eyre this power relationship is reversed somewhat in the end – Rochester is blinded and disfigured in the fire at Thornfield Hall and needs Jane’s assistance – only after this can she say, ‘Reader, I married him’ at the end – another iconic line. Maxim is emotionally scarred after Manderley’s fire and needs our Jane to aid him in his ‘exile’ and she will keep his secret forever.

[SPOILER – BELOW I DISCUSS THE ENDING]

It is telling, that when J finds out about Maxim killing Rebecca, she is not shocked, is not appalled, only says over and over again ‘he did not love Rebecca’ – there is no moral issue in this murder, only an emotional one. Du Maurier has painted Rebecca so blackly that we want Maxim to get away with it, so J can get her reward i.e. to be with him and to have him confess his love for her.

Which brings me to my next gripe – the portrayal of Rebecca. Rebecca has to be beautiful and glamorous so the more ordinary J is jealous of her and her feelings of inadequacy heightened. Mrs Danvers taunts J with all the lovely things in Rebecca’s room that she keeps as a shrine to her. Rebecca keeps herself well-groomed, wears expensive clothes, goes up to London to shop. So? She’s an upper-class woman married to an extremely wealthy man. Maxim would have known this about her, as well as her love of the good life before he married her. We are supposed to believe she can make herself charming to everybody and she hoodwinked him. On her honeymoon on the French Riviera she tells him the truth (at the very spot he takes J on their first outing – on a cliff overlooking the sea). Maxim is so incensed that he contemplates throwing Rebecca off – nice! Never heard of divorce, Maxim? Rebecca’s ‘sin’ and what makes the shooting of her understandable, and forgivable to our heroine, is that she has some unspecified unsavoury tastes. As far as we can tell, these are parties, drink and promiscuity – the same ‘sins’ that if a man showed them, the wife would be expected to put up with them. Maxim has to kill her because she’s taken to inviting her not-very-nice friends down to his beloved Manderley. By the way, no one else has an inkling Rebecca is anything other than wonderful but to rub it in Du Maurier has her hit on Maxim’s sister’s portly, old fuddy-duddy husband, Giles, possibly for a laugh, possibly because she’s insatiable – she also has an affair with her smarmy cousin, Favell, again, for no understandable reason. In fact, Rebecca is even at fault in her own death, smiling as Maxim shoots her in a sort of suicide-by-husband, we are supposed to believe. The one thing that does make her plainly reprehensible is the threat to put Ben, an intellectually disabled man, ‘in the asylum’ if he breathes a word of her goings on in the cottage on the bay. She should have been able to charm him the way she did everyone else but Du Maurier needs this threat to build tension in the inquest section near the end. I’m sure Du Maurier does not intend it, but Rebecca’s venality here is offset somewhat, by our heroine (and Maxim) referring to Ben as the ‘idiot’ and imputing him with a ‘sly smile’.

This is not to say Rebecca is not a good book in many ways. I admire the control du Maurier has over the story – the structure is masterly, the reader is led down several garden paths, and the atmosphere is beautifully evoked. Many novels (and novelists) go out of favour because of the values they inhere but some, such as Rebecca, manage to dodge this. Perhaps the novel is not seen as literature, and so it gets a leave pass, or we convince ourselves that a life of comfortable idleness abroad is sufficient penance for a murderer and his wife (an ‘accessory after the fact’). But, who cares? She gets her man and that’s the main thing.