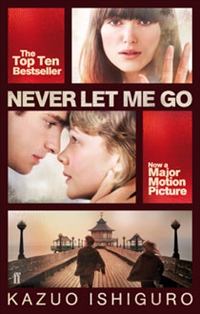

My book reading for 2011 was rather sparse for some reason – so many books in the world, so very few read. The top book from those I read this year is Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. This was the novel that affected me the most and, I thought, was the most masterfully conceived and written. A quite good film was made of it and released during the year, and it is well worth checking out but, of course, it’s better to read the book. The book is written in the somewhat prosaic voice of Kathy who is an orphan (we think) living in a boarding school in the English countryside. From her limited perspective we find out more about the children in, what becomes more and more apparent, is a very strange institution. The reader is very subtly brought into this unsettling world, so that the horrifying is normalised. I thought the novel was beautiful, sad and very challenging on a number of levels.

My book reading for 2011 was rather sparse for some reason – so many books in the world, so very few read. The top book from those I read this year is Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. This was the novel that affected me the most and, I thought, was the most masterfully conceived and written. A quite good film was made of it and released during the year, and it is well worth checking out but, of course, it’s better to read the book. The book is written in the somewhat prosaic voice of Kathy who is an orphan (we think) living in a boarding school in the English countryside. From her limited perspective we find out more about the children in, what becomes more and more apparent, is a very strange institution. The reader is very subtly brought into this unsettling world, so that the horrifying is normalised. I thought the novel was beautiful, sad and very challenging on a number of levels.

In supporting short stories I commit to reading one short story a week. Not a lot, I know, but I find I’m always reading a novel and it’s easy to forget stories. There is an idea going around that short fiction will come into its own in the age of the smart phone and the tablet, peoples’ busy lives and a commuting culture. Let’s hope so. Okay, my favourite short story for the year is one I just chanced upon while browsing the net. The story is “One Last Winter Moment” by Kathleen Kennedy and this was publishing online in the Canadian Room Magazine. So you can enjoy it yourself here. It’s poignant, sad and beautifully written.