Arcturus Crime Classics have recently republished (Hinkler Books, Heatherton, Victoria) classic crime novels from the 1930s to 70s of “once famous but now neglected’ writers. I bought 5 for $20 at my local newsagent and what a bargain they have turned out to be.

Arcturus Crime Classics have recently republished (Hinkler Books, Heatherton, Victoria) classic crime novels from the 1930s to 70s of “once famous but now neglected’ writers. I bought 5 for $20 at my local newsagent and what a bargain they have turned out to be.

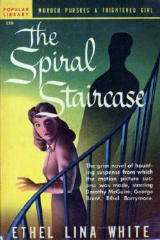

Some Must Watch by Ethel Lina White was published in 1933 and inspired the film Spiral Staircase directed by Richard Siodmark.

On page 1 we are introduced to Helen who is walking back to the lonely country mansion The Summit (where she works as lady’s help) just as dusk draws. The setting includes a “blocked view”, mud, “barren sepia mounds” and a “fine spit of rain”. Helen is introduced as “facing hard economic facts” and “not prone to self-pity”. She also has an optimistic, joyful attitude to life and is small, frail, “pale as a slip of crescent moon”. So far, so good. We have a heroine who is small and frailish but plucky and realistic in a gloomy inhospitable landscape and set out, at least for now, for home. We know it is a crime classic, so it would bode well if she could hold her own. Oh, and just at the bottom of page 1, we are told Helen likes to ask strangers the time of day, as she has a specialised interest in looking at their watches. No doubt this slightly odd interest may help her when the time comes. I realise I was subconsciously thinking that as I look back on the first page after being taken on a whirlwind ride through Helen and the other characters’ (whose very unreliable characteristics emerge and submerge) eventful night while boxed in in a gale-whipped country house set in a black and shifting landscape.

On arrival at The Summit, Helen appreciates the warm well-lit glow and human busyness in the house, barricaded against the storm. In fact the ritual of trying to tie up the shutters and lock the doors (one of her tasks) recurs throughout the book. White’s black, spiny, discomforting imagery is carefully salted throughout, not holding up the pace one whit. I particularly liked the image of the coal scuttle in the old lady’s room where each piece of coal is wrapped in white tissue paper (to minimise upsetting noise). I loved her imagery of trees and the plantation outside the house as alive, with tree trunks splitting into two, one half a hiding man. In fact this imagery reminds me of a Stephen King – I am sure he has studied White on to slowly build terror without the reader even being aware of the slow ratchet of expectation.

The people inhabiting the house are a wonderful set – the housekeeper and her husband, the lady’s nurse, the family and Helen. Their characters are effortlessly developed through action and dialogue, but description, however, cannot be relied upon. The replacement nurse with her masculine appearance and jealousy, the apparently malevolent (is she really so helpless?) old lady, the student’s inexplicable resistance to the sexy daughter-in-law’s advances and the housekeeper’s weakness for brandy (in a teetotal house) all start to breach the walls of the house, as the murderer prowls ever closer.

Helen is the third-person narrator and the writing at the end of the book becomes more fractured as Helen’s stout little character becomes less and less reliable, and more self-pitying. But her willingness to compromise as the situation fatefully unravels is probably realistic. One thread of sanity and safety runs through the book – Helen’s romance with the doctor whose comfortable authority and entrance to the barricaded house becomes unreliable. And even then, as we expect the lover to come to the rescue, it is not he who resolves the story, and the breached integrity of the house itself is seen in reverse.

Helen is the third-person narrator and the writing at the end of the book becomes more fractured as Helen’s stout little character becomes less and less reliable, and more self-pitying. But her willingness to compromise as the situation fatefully unravels is probably realistic. One thread of sanity and safety runs through the book – Helen’s romance with the doctor whose comfortable authority and entrance to the barricaded house becomes unreliable. And even then, as we expect the lover to come to the rescue, it is not he who resolves the story, and the breached integrity of the house itself is seen in reverse.

I could not put this story down, even at the end where the story fracturing slightly. Helen’s ‘specialised interest” actually turns out to be curiosity, a craving for novelty that has its place in the fateful unfolding of events. White makes setting up her characters and the threatening nothing-is-as-it-seems world almost seamless from the first page. From the “barren sepia mounds, blurred by a fine spit of rain” and “lumpy” distant thunder, to Helen’s stout character which welcomes each day, ready to “shred its interest from every hour”, we snuggle down, feeling safe, we are in the hands of a competent story teller. I gulped down each carefully placed word, each fateful, destined twist and turn, each misdirection, in huge satisfying drafts. That’s how you take your reader on a whirlwind ride!

Another Arcturus Crime Classics is Trial and Error by Anthony Berkeley also known as Francis Iles who wrote After the Fact, filmed by Hitchcock as Suspicion. Trial and Error is the story of Mr Todhunter who finds he has three months to live would like to distinguish himself in an otherwise humdrum life by doing a civic good before he dies, to wit the murder of a thoroughly nasty person!

Tania’s review.