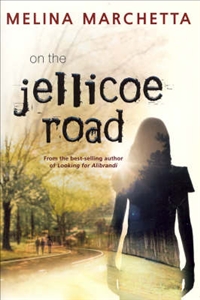

For some reason I read Melina Marchetta’s Looking for Alibrandi when it came out in 1992, YA in a contemporary Australian setting not really being my thing, and I was surprised by how much I enjoyed it. Although the book, and the film that followed it, were very successful, it took Marchetta 11 years for her next book Saving Francesca to be published. This was followed by On the Jellicoe Road in 2006. I noticed this book because I was attracted to the cover. Something about it reminded me of country towns with big shady trees, gravel roads and empty school playgrounds. I spent two years of my senior schooling at Leeton in the Riverina and I have a nostalgic pang for the flat land, big skies and swimming in the Murrumbidgee. I hadn’t twigged until I finally got around to reading On the Jellicoe Road that the book is set in that area.

For some reason I read Melina Marchetta’s Looking for Alibrandi when it came out in 1992, YA in a contemporary Australian setting not really being my thing, and I was surprised by how much I enjoyed it. Although the book, and the film that followed it, were very successful, it took Marchetta 11 years for her next book Saving Francesca to be published. This was followed by On the Jellicoe Road in 2006. I noticed this book because I was attracted to the cover. Something about it reminded me of country towns with big shady trees, gravel roads and empty school playgrounds. I spent two years of my senior schooling at Leeton in the Riverina and I have a nostalgic pang for the flat land, big skies and swimming in the Murrumbidgee. I hadn’t twigged until I finally got around to reading On the Jellicoe Road that the book is set in that area.

Nostalgia aside, I loved On the Jellicoe Road. The novel has a complex structure set around a mystery that resolves itself slowly through the eyes of our heroine, seventeen year old Taylor Markham. Marchetta’s brilliance is to make the reader totally accept Taylor’s viewpoint. It’s hard to describe the plot without giving away details that would make the unravelling of the mystery less satisfying. Suffice to say it deals with a modern day group of teenagers, some from a boarding school, some from the town and some from a group of cadets who camp there every year. The various groups are involved in a territory war every summer. Taylor is head of her ‘house’ at the school and she has to lead the school’s group against the townies and cadets. The enclosed nature of the ‘wars’ and the lack of adult interference is expertly handled by Marchetta but we soon find out the wars are a backdrop to Taylor discovering things about her past that for unknown reasons are being kept from her. The pleasure of the novel is all in the unfolding, and in the development of the relationship of the teenagers (or should I say young adults?), Marchetta’s forte. There are really two stories in one – what happens to five friends after a tragedy twenty years before and how this interweaves with the present day characters. I found this relationship cryptic to begin with – it was brave of Marchetta to just go with the story, confident her YA readers will follow Taylor and be patient enough to let the scenario play out at its own pace.

I was surprised, given the many awards Marchetta has garnered, that in Australia On the Jellicoe Road has only won a category of the 2008 WA young readers award. Last year she won the US Michael Printz Award for excellence in young adult literature, an award associated with the American Library Association. Why, I wonder, is Craig Silvey’s Jasper Jones categorised as literary fiction, and short-listed for the Miles Franklin Award, and On the Jellicoe Road relegated to YA? Could it be that Silvey’s book has a male protagonist and overtly references literary classics?

I was surprised, given the many awards Marchetta has garnered, that in Australia On the Jellicoe Road has only won a category of the 2008 WA young readers award. Last year she won the US Michael Printz Award for excellence in young adult literature, an award associated with the American Library Association. Why, I wonder, is Craig Silvey’s Jasper Jones categorised as literary fiction, and short-listed for the Miles Franklin Award, and On the Jellicoe Road relegated to YA? Could it be that Silvey’s book has a male protagonist and overtly references literary classics?

Apropos of the cover I loved so much, the B format cover makes the book look like a soft relationships novel for teenage girls and has none of the sense of place and intrigue of the first cover. As a point of contrast, on the cover for Marchetta’s latest book, The Piper’s Son, the publisher has gone 180 degrees the other way – a monochrome photo of a young man walking down a depressing looking inner-city street. It shouts ‘take me seriously’. I checked just in case the book was categorised as adult fiction. But no, despite the protagonist being in his late teens or early twenties, it’s still YA according to Penguin.

We’ve got the Booker, the Pulitzer, the Commonwealth, Dublin Impac, the Orange and now there is a prize for South Asian writers. The DSC prize is worth US $50,000 and is to “raise awareness of South Asian culture around the world”. It is open to works by authors of “any ethnicity from any country which predominantly features themes based on South Asian culture, politics, history, or people”. South Asia is defined as “India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives and Afghanistan”. Interestingly the shortlist includes Atlas of Unknowns by Tania James, a US citizen born and bred. It’s a novel about two Indian sisters, one of whom takes up a scholarship to New York.

We’ve got the Booker, the Pulitzer, the Commonwealth, Dublin Impac, the Orange and now there is a prize for South Asian writers. The DSC prize is worth US $50,000 and is to “raise awareness of South Asian culture around the world”. It is open to works by authors of “any ethnicity from any country which predominantly features themes based on South Asian culture, politics, history, or people”. South Asia is defined as “India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives and Afghanistan”. Interestingly the shortlist includes Atlas of Unknowns by Tania James, a US citizen born and bred. It’s a novel about two Indian sisters, one of whom takes up a scholarship to New York.