A Flavia de Luce Mystery

A Flavia de Luce Mystery

Orion Books 2009

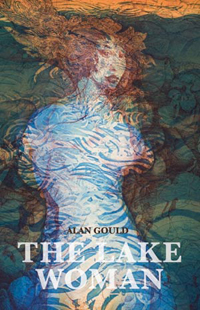

Recipe by Alan Bradley

The Sweetness:

- Venerable old English country pile, seat of the de Luce family

- Set post-war 1950s and pre- so many things

- First person heroine (Flavia): hyper intelligent, monstrously well-educated and one of three Mitford-like sisters

- Flavia has her own well-stocked chemistry lab! Yay!

- Absent parents, that mandatory element of the 1950s children’s adventure story. Yay! Dad is closeted with his musty old stamp collection and mother is a feminist aviatrix and adventuress who is presumed dead – perfect!

- Ladles full of literary, musical and art references

- Liberal sprinkling 1950s brand names and events

- A murder to solve

- Baddies

- Country-style coppers who, nonetheless, outpace Flavia (refer to Agatha Christie here about the perils of underrating country coppers)

- Flavia’s father has a secret in his past which is sending a long shadow into the present

- Humdinger red herring

Pie crust

- Standard cosy murder mystery structure

- Play fair with reader

Method:

- Mix sweet ingredients very, very carefully and place in piecrust.

Review

Mature, Scottish (Zimbabwean-born), white, male Alexander McCall Smith created a believable and charming black, Botswanan, traditionally-sized female detective in The Full Cupboard of Life. Can mature, white, Canadian male Alan Bradley do the same with his overflowing cupboard of ingredients for his white, English, 11 year-old Flavia De Luce series, and this book in particular?

Let’s see what the reviews on my book cover said:

- “Cross between Dodie Smith… and the Addams family”;

- “A dark Nancy Drew set in a gothic Midsomer”.

Yikes! Just goes to show that if crème caramel is nice and liquorice allsorts are nice, a caramel allsort pie is not necessarily going to work. By the way, I could not see anything remotely like Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle or 101 Dalmatians here. Nor the Addams family, thank goodness.

It is easy to be delighted by the precocious Flavia whose chemical and elemental asides are fascinating and often pertinent…(which describes what happens when the yellow prussiate of potash is heated with potassium to produce potassium cyanide). She is humorous and as omnivorously intelligent and educated as you wish we all could be. However, I think this sort of 11 year-old would be more appropriate in a child fantasy/mystery ( like Lemony Snicket stories for example). It becomes a bit of a stretch here in stock standard cosy land, with a first person narrator. The 1950s references are, I am sure, accurate, but seemed more like a banner strung across the stage than of the play itself. The mystery is delightfully tangled and necessitates so much bicycling by Flavia on her trusty steed Gladys (a Raleigh for those thousands of us who remember) that I felt for her 11 year-old legs.

With so much to like and a real desire on my part to unravel the mystery, why did I find this an unsatisfying read? Has Bradley just thrown too much delight and sweetness at a fairly slight theme? Flavia has her own website and lots of fans who have no trouble at all with a 1950s 11 year-old stuffed to the gills with feminism, chemistry, D’oyley Carte operettas, literature, art etc. I can see where her mischievous and humane sides are given a run in her relationship with her sisters but it’s all a bit strained and cursory.

The Ladies Detective Agency series has characters with real humanity and a moral viewpoint that informs them and forms part of the South African setting that McCall Smith obviously loves and understands, warts and beauty alike. Bradley needs to develop that kind of core for his heroine in her very English setting so her humour and intelligence can be grounded in the setting that gives rise to her mystery. It lacks heart and in the end is less a pie, perhaps, than a glorious jumble of trifle, needing more control to blend these delicious ingredients into a coherent dish.

Review by Tania