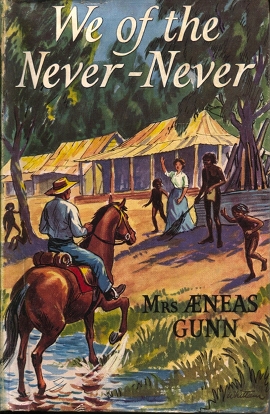

We of the Never Never is one of those Australian classics, I never got around to reading in my school years, thinking it would be too twee. How wrong was I. We of the Never Never was not at all what I expected. I thought it would be a family story, they’d be children involved, it would cover the establishment of a station, that there would be trials and tribulations and Jeannie Gunn would grow to love the land and nature etc. etc. In fact, the novel does not read like a novel at all; it is basically a series of sketches written in an arch, comic, ironic style – reminiscent of what was printed in the newspapers of the time, or in the Bulletin.

We of the Never Never is one of those Australian classics, I never got around to reading in my school years, thinking it would be too twee. How wrong was I. We of the Never Never was not at all what I expected. I thought it would be a family story, they’d be children involved, it would cover the establishment of a station, that there would be trials and tribulations and Jeannie Gunn would grow to love the land and nature etc. etc. In fact, the novel does not read like a novel at all; it is basically a series of sketches written in an arch, comic, ironic style – reminiscent of what was printed in the newspapers of the time, or in the Bulletin.

The story starts with ‘the Missus’ (based on Jeannie Gunn herself) arriving at Katherine, having come from Darwin with her husband, on the way to Elsey Station where ‘the Maluka’ (a thinly disguised Aeneas Gunn) is the new manager. A white woman is unheard of ‘in the interior’ and the bush telegraph (the station men) makes it clear they don’t want any woman bringing her fussy ways. The dramatic tension rests on whether the Missus will make it or not. There are undoubted hardships, but the Missus first shows her pluck by agreeing to be winched across a swollen river, and not complaining about it. In fact, the Missus takes most things in good spirit and is not above mocking herself.

When they reach Elsey things are not much better and the ‘homestead’ is really an open frame with the verandah being the only thing that is covered. The men, though, are mighty surprised she’s turned up at all. That she is willing to put up with hardships, earns, if not respect, then at least, not open hostility. The strange thing is that the Missus has her husband there but he doesn’t seem interested in smoothing things out for her, or taking her side against the blokes. He makes jokes at her expense and looks on wryly when she has to face new trials. Most annoyingly of all, he likes t call her ‘little ‘un’ (apparently Jeannie Gunn was slight and only 5 feet tall). But the Missus takes it all in good humour and presents these early slights in an entertaining manner.

Before too long things look up a little. They get a Chinese cook, Cheon, who is a born organiser, their belongings finally come in by bullock team after the rivers have gone down, and Johnny, a rough carpenter starts to work on walls and a ceiling but this work is constantly interrupted by more important things like going out bush for branding or mustering. Despite some little comforts, like sheets, things are extremely primitive. I was shocked that they thought it was perfectly all right to shoot enough wild birds to get feathers to makes some pillows (the billabong surrounds were, after all, thick with them, birds that is).

One of the most irritating characters is Dan who thinks it soft that anyone should want live in a house. He thinks the Missus needs educating and much is made of this ‘education’. Of course Jeannie Gunn makes it all sound so humorous: as the Missus is exposed to hardships, Dan chuckles – that’s educating her. Like women entering a male-dominated profession, the Missus has to become one of the boys, and there is nothing they do that she disapproves of, even dog fighting. The novel is really a paean of praise, to the bush folk i.e. bushmen.

Perhaps this makes it sound less sophisticated than it is. Jeannie Gunn is a talented writer who evokes well the environment she finds herself in, she has a comic ear and no one can doubt the verisimilitude of what she describes. There is a reason that this novel was a best seller and was revised for use in schools. I wonder what the kids thought of it, though. As far as I can see there’s not a lot that they’d be interested in – while there is drama in small scenes, wild bulls rampaging through a camp and scrambling up trees to escape them, for example, as a whole it is episodic with little unfolding story.

These days, it seems dated and reads like a piece of documentary about colonial life and early settlement of the interior of the Northern Territory. I have to say I found the treatment of the Chinese condescending and verging on racist. Gunn gets away with it with Cheon because he is such a great, larger-than-life character but the only quasi-villains in the whole book are some Chinese cattle buyers.

The treatment of Aboriginal people is also problematic although, I suppose, at least, they are a part of the tale and not excised from it – like the invisibility of Aboriginal people in much of the literature of the time. But I was shocked, totally, when one of the men mentions they need to go on a ‘nigger hunt’. Okay, it was not a massacre, just moving on some Aboriginal people from where they were camping along the river (no doubt on their own land) but the term must have held an echo of real violence to the men using it at the end of the 19th century. Gunn, in typical fashion, makes light of it and the Aboriginal people have left before the ‘hunting’ party gets there anyway. But today, it is hard not to feel a chill at that term used so casually in 1902 (and accepted in 1956).

In fact a paper written in 1990 by Peter Forrest about the settlement of the NT says that there were massacres of Aboriginal people in the Territory in 1903 (after Jeannie Gunn left) because they were accused of harassing and killing cattle that were being introduced to new areas. Forrest says: ‘According to strong oral tradition in the area, one of the ringleaders in these episodes was Jock MacLennon, the Sanguine Scot [one of the characters in the novel]’. I was also fascinated to read Forrest’s thesis that one of the reasons the men were so against white women coming to the stations was a fear they would interfere with the men’s sexual exploitation of Aboriginal women.*

Gunn’s narrative treatment of the ‘station blacks’ was probably enlightened for the day. She shows that they are part of the everyday life of the station – with the ‘boys’ being stockmen and the ‘lubras’ working in the house, or at least some of them – there is some comedy made of the competition between the women to get jobs in the homestead. There is a symbiotic relationship – the Aboriginal people get food and a place to live (in humpies in their own camp) and the station gets workers. Of course, the whites do not remotely question their right to the station, or to exploit Aboriginal people as workers. The Aboriginal people are seen as humorous, and childlike (although, I have to admit, so are many of the white people).

My edition of the novel, published in 1956, still had reference to the *n* hunt but I believe, in the recent reissue, this was expurgated which is a pity because it’s important to realise what attitudes were in 1908 when the book was first published, not to mention the whole issue of censoring literary works. I also understand the 1982 edition, which was published along with Gunn’s only other book, The Little Black Princess, also had these references edited out.

There is not a lot of description of the natural environment in the novel but what there is, is beautiful and evocative. Elsey station no longer stands but there is a replica at Mataranka in the NT and the quite stunning warm mineral pools Gunn describes below are still there in the national park (Elsey station was finally handed back to the Mangarayi people in 2000) – the water is preternaturally clear and, set among palms in the arid environment, they are truly as gem-like as Gunn paints them in the book:

Clear, beautiful, limpid … set in undulating field of emerald-green mossy turf, shaded with graceful foliage and gleaming in the sunlight with exquisite opal tints – a giant necklace of opals, set in links of emerald green, and thrown down at hazard, to fall in loops and curves within a forest grove.

* They of the Never Never, Northern Territory Library Service 1990