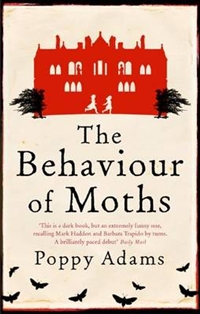

The Behaviour of Moths

The Behaviour of Moths

Poppy Adams

One of the thing guidebooks for writing like to emphasise is the compact with the reader. The writer has to play a fair game, no matter how tricksy, convoluted or abstruse they might be to get their story told. At the end of The Behaviour of Moths I had the distinct feeling that Poppy Adams had not kept her contract with me. I can’t accuse her of not laying the groundwork for her denouement because she does, quite carefully. We know from the beginning that her narrator, Ginny, is quirky and obsessive, but it is a fun quirkiness and an endearing obsessiveness (this obsessiveness is later channelled into her work as a lepidopterist, following her father into the field hence the “behaviour of moths”).

The novel starts with Ginny in old age waiting for the return to their family mansion of the sister she hasn’t seen for 47 years. The reason for the estrangement is spooled out in flashbacks over the space of several days. Adams has a facility with words and a wonderful ability to  evoke scenes and people through the mordant prism of Ginny’s eyes. For the most part I was enthralled with this book (who would have thought descriptions of moth collecting, dissecting, preserving etc could be so engaging?) I loved the portrayal of the sisters’ relationship, the mother and the father and the house and countryside. So why did I feel betrayed by the ending?

evoke scenes and people through the mordant prism of Ginny’s eyes. For the most part I was enthralled with this book (who would have thought descriptions of moth collecting, dissecting, preserving etc could be so engaging?) I loved the portrayal of the sisters’ relationship, the mother and the father and the house and countryside. So why did I feel betrayed by the ending?

Of course there has to be dark secrets and mysteries and, of course, the seeds for unravelling these have to be sewn throughout the narrative, and Adams does do this quite deftly. She does, for example, have a family doctor who takes an inordinate interest in Ginny, annoying her with his questions and attentions. She does have a terrible accident befall Ginny’s sister and Ginny overhearing her mother complaining that she (Ginny) shows little emotion over it.

Ginny, as the narrator, is able to explain most things away to the reader but we remain wary, as we should. It is the sign of a great (rewarding) writer that they hold these things in balance in a plot. The reader has to be drawn forward in the mystery, be taken down plausible roads and then be left there disoriented as something unexpected happens, only to be reassured and picked up again. Sarah Waters did this masterfully in The Little Stranger. That book, too, left me with the sense I’d been led up the garden path but when I looked back over the story I couldn’t pinpoint where I’d been misled so deftly was the thing knitted together. In the case of The Behaviour of Moths there was a place near the end where Adams used an unfair device to keep information from the reader. I won’t spoil the ending but it didn’t sit comfortably with me. Okay, an ending doesn’t have to be comfortable but it has to feel right. That said, as a debut novel, The Behaviour of Moths is accomplished, enjoyable and beautifully written.