Apart from the big writers’ festivals, writers’ sessions at fairs and community events are popping up more and more. There’s been a writers’ tent at the Newtown festival in Sydney for a few years, for example. On holidays recently I was in the little fishing village of Crail in Scotland during its annual festival, this year celebrating 700 years of becoming a royal burgh under Robert the Bruce. Amongst the parades, stalls, competitions and musical events, there was a “meet the writers” session in the kirk hall. On stage was the usual ill assortment of writers – a crime writer Gillian Galbraith, general fiction writer Robin Pilcher (son of romance writer Rosamund) and historian Alistair Moffat. Gillian was a lawyer before becoming a crime writer and she was considered and serious in her answers to questions like “how much of you is there in your detective heroine?” Robin Pilcher, by contrast, was flamboyant, erratic and bombastic. Coming from a PR background he was intent on giving “his readers” what they wanted which seemed to be anodyne, bland, human interest in the vein of Bryce Courtenay. Pilcher made number 1 on the New York Times best seller list, though, so who am I to make fun? He must have thought his one-man self-justification show was going down well because he went horribly overtime leaving poor old Alistair Moffat, only a few minutes. The contrast could not have been greater as Moffat read out the first chapter of his book The Highland Clans. Using the battle of Culloden as his starting point and following the POV of a young boy watching the fight from a vantage point, it was a wonderful example of non-fiction writing, He skilfullybrought together the background stories of the various clans gathered there that day. We were all a bit bemused as we walked out into the pale sun of a Scottish mid-summer’s day.

Apart from the big writers’ festivals, writers’ sessions at fairs and community events are popping up more and more. There’s been a writers’ tent at the Newtown festival in Sydney for a few years, for example. On holidays recently I was in the little fishing village of Crail in Scotland during its annual festival, this year celebrating 700 years of becoming a royal burgh under Robert the Bruce. Amongst the parades, stalls, competitions and musical events, there was a “meet the writers” session in the kirk hall. On stage was the usual ill assortment of writers – a crime writer Gillian Galbraith, general fiction writer Robin Pilcher (son of romance writer Rosamund) and historian Alistair Moffat. Gillian was a lawyer before becoming a crime writer and she was considered and serious in her answers to questions like “how much of you is there in your detective heroine?” Robin Pilcher, by contrast, was flamboyant, erratic and bombastic. Coming from a PR background he was intent on giving “his readers” what they wanted which seemed to be anodyne, bland, human interest in the vein of Bryce Courtenay. Pilcher made number 1 on the New York Times best seller list, though, so who am I to make fun? He must have thought his one-man self-justification show was going down well because he went horribly overtime leaving poor old Alistair Moffat, only a few minutes. The contrast could not have been greater as Moffat read out the first chapter of his book The Highland Clans. Using the battle of Culloden as his starting point and following the POV of a young boy watching the fight from a vantage point, it was a wonderful example of non-fiction writing, He skilfullybrought together the background stories of the various clans gathered there that day. We were all a bit bemused as we walked out into the pale sun of a Scottish mid-summer’s day.

Silvery temple

Craig Silvey continues his winning run, getting the Australian Book Industry Award for best literary fiction book of the year (Jasper Jones), and Peter Temple (Truth) follows up his Miles Franklin by getting the best general fiction book gong. A small number of books seem to be chasing each other around the award circuit, with Alex Miller and David Malouf missing out. The ABIAs tend to go to books that sell (I’m sure they have to have to have literary merit as well).

Review – Survivor

Chuck Palahniuk, WW Norton, 1999.

Review excerpts at the start of this book refer to Palahniuk in the same breath as Camus, Vonnegut, DeLillo and Pynchon, if that is any help to what you think will be inside. Survivor is structured, Tristram Shandy-like as a chapter countdown of a life during the seconds to a plane crash, except that Tristram Shandy is being born, and our survivor is the remnant of a suicide cult recording his last moments into the plane’s flight recorder as it crashes.

Review excerpts at the start of this book refer to Palahniuk in the same breath as Camus, Vonnegut, DeLillo and Pynchon, if that is any help to what you think will be inside. Survivor is structured, Tristram Shandy-like as a chapter countdown of a life during the seconds to a plane crash, except that Tristram Shandy is being born, and our survivor is the remnant of a suicide cult recording his last moments into the plane’s flight recorder as it crashes.

I wouldn’t say Palahniuk is another Fielding but he has an affinity for the lonely, salty lives at the edge of mainstream society. In Survivor the protagonist narrator is gradually revealed to us through his unique take on the world, influenced by the role the cult gave him in the “outside” world. Two of the United States’ cultural creations, the insular, non-taxpaying religious cult and the mass market collude and collide here. Both feed off vulnerability, brainwashing, hope and someone else’s money in your pocket, and lots of it.

The protagonist, whose name is gradually revealed, comes from a labouring cult and the book is peppered with the handy home hints the cult followers are trained in so they can be desirable cheap labourers in the outside world and send the money back to the cult. Potential employers of the cult followers want to know how to eat lobster, how to behave as if civilised and to avoid cleaning up their own messes. Palahniuk’s whingy-whiner hero could be any one of us with our culturally-induced problems (need more plastic surgery, need Viagra, need love, need bigger/more everything) but he has the answer for our existential angst – kill yourself. It is programmed into cult members. It was Camus, I think, who thought suicide was the one serious philosophical problem: a lack of courage in the face of the ultimate meaninglessness of everything, as only we, ourselves, can seek our own meaningfulness. And what an interesting quest that is.

Survivor is skilfully structured and reveals a compellingly bizarre world, leavened with black humour. About three quarters of the way through I thought the railing against modern society and sexual grossness grew soggy. I’m all for railing and inveighing, but Palahniuk moves at a gulping speed and it feels a little undigested. However, Palahniuk is a good enough writer to fashion sustained quality from the raw material of excess and greed, and a clever enough one to depict a convincingly a Kafkaesque world of ever-closing nightmare.

An astute social commentator, expect no mercy from Palahniuk. This is a read for those who relish their social commentary funny and sharp in a picaresque setting relentlessly careening to the edge.

Reviewed by Tania

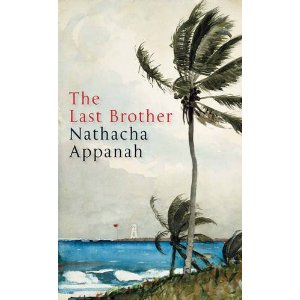

The Last Brother

I’d like share the lovely cover for Nathacha Appanah’s novel The last Brother. Appanah is from Mauritius but now lives and writes in France. The Last Brother is a tale of the friendship of two boys: Raj, a native of Mauritius, and David a young Jewish boy incarcerated on the island after a group of refugees fleeing Europe in 1945 are interned there. Appanah beautifully evokes the lushness of the island but also the harshness of life for both of the boys. The story is framed by the older Raj who looks back with guilt on what occurred on the island. There is poignancy in the portrait of Raj as a boy, not quite aware of what is going on, and who is the victim of a violent father. But I never bought his love for David whom he befriends when he spends time in the prison hospital (Raj’s father works as a prison guard). David is never a fully realised character – his main attribute being his blonde fly-away hair and uncoordinated body. Appanah suggests that David is a substitute brother to Raj after Raj’s other brothers are killed in a flash flood (hence David is really the “last brother”) but I thought the relationship was forced. Nevertheless this is a short, fable-like book, and gives a rich sense of another life. I bought the book on the strength of the wonderfully evocative dust jacket which I’ve framed. Does that count as vandalism against a book? It still has the underneath plain green hard cover …

I’d like share the lovely cover for Nathacha Appanah’s novel The last Brother. Appanah is from Mauritius but now lives and writes in France. The Last Brother is a tale of the friendship of two boys: Raj, a native of Mauritius, and David a young Jewish boy incarcerated on the island after a group of refugees fleeing Europe in 1945 are interned there. Appanah beautifully evokes the lushness of the island but also the harshness of life for both of the boys. The story is framed by the older Raj who looks back with guilt on what occurred on the island. There is poignancy in the portrait of Raj as a boy, not quite aware of what is going on, and who is the victim of a violent father. But I never bought his love for David whom he befriends when he spends time in the prison hospital (Raj’s father works as a prison guard). David is never a fully realised character – his main attribute being his blonde fly-away hair and uncoordinated body. Appanah suggests that David is a substitute brother to Raj after Raj’s other brothers are killed in a flash flood (hence David is really the “last brother”) but I thought the relationship was forced. Nevertheless this is a short, fable-like book, and gives a rich sense of another life. I bought the book on the strength of the wonderfully evocative dust jacket which I’ve framed. Does that count as vandalism against a book? It still has the underneath plain green hard cover …

Truthfully yours

So Truth  did win the Miles Franklin. Good on them for chosing a crime novel, though a quite literary one. The judges did point out the serious themes, and Temple’s style is spare and eschews the cliche of some crime fiction, so I don’t think this is a “dumbing down” of the award, or an attempt to make the winning book a more “accessible” one. For the record, the judges’ comments were: Temple “takes a popular genre and transforms it into a radical literary experiment in realism and fiction”, and the novel is “written with all the ambiguity and moral sophistication of the most memorable literature”.

did win the Miles Franklin. Good on them for chosing a crime novel, though a quite literary one. The judges did point out the serious themes, and Temple’s style is spare and eschews the cliche of some crime fiction, so I don’t think this is a “dumbing down” of the award, or an attempt to make the winning book a more “accessible” one. For the record, the judges’ comments were: Temple “takes a popular genre and transforms it into a radical literary experiment in realism and fiction”, and the novel is “written with all the ambiguity and moral sophistication of the most memorable literature”.

Truth will out

Or will it? The Miles Franklin award will be announced this Tuesday, 22 June and I’m having a punt on the outcome. I’m going to go for Peter Temple ‘s Truth. Okay, I haven’t read it but I haven’t read any of the others on the short list either. I’m going by deduction, my dear Watson. I admire and respect Sonya Hartnett but I don’t think her YA novel Butterfly will be seen as substantial enought to win. I suspect she is on the short list because her large body of work in children’s literature is generally not acknowledged in this country, except in the CBCA awards (she won the very lucrative Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award from Sweden). Craig Silvey won the 2009 Indie Book Award for Jasper Jones but ditto for him although this YA novel is proving very popular. Alex Miller is substantial, though personally I find his novels a bit too consciously literary, but I hear Lovesong is not one of his best (see Angela Meyer’s blog ) and Miller has won the Miles Franklin twice before. I don’t know about The Book of Emmett (but I like the cover): it has had good crits but it’s a debut novel with the dour subject matter of an abusive father and the cost to his children. That leads me via elimination to Truth. I tried to read The Broken Shore after all the good reviews but I didn’t like it. However, after winning a raft of crime writing awards it may be time for Peter Temple to win a literary fiction one. His writing does appear to cross over into the literary and Truth has been universally praised.

‘s Truth. Okay, I haven’t read it but I haven’t read any of the others on the short list either. I’m going by deduction, my dear Watson. I admire and respect Sonya Hartnett but I don’t think her YA novel Butterfly will be seen as substantial enought to win. I suspect she is on the short list because her large body of work in children’s literature is generally not acknowledged in this country, except in the CBCA awards (she won the very lucrative Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award from Sweden). Craig Silvey won the 2009 Indie Book Award for Jasper Jones but ditto for him although this YA novel is proving very popular. Alex Miller is substantial, though personally I find his novels a bit too consciously literary, but I hear Lovesong is not one of his best (see Angela Meyer’s blog ) and Miller has won the Miles Franklin twice before. I don’t know about The Book of Emmett (but I like the cover): it has had good crits but it’s a debut novel with the dour subject matter of an abusive father and the cost to his children. That leads me via elimination to Truth. I tried to read The Broken Shore after all the good reviews but I didn’t like it. However, after winning a raft of crime writing awards it may be time for Peter Temple to win a literary fiction one. His writing does appear to cross over into the literary and Truth has been universally praised.

Oranges are the fruit

At least for Barbara Kingsolver whose latest novel The Lacuna has won the 2010 Orange Prize for fiction by women. The prize is awarded to “the woman who, in the opinion of the judges, has written the best, eligible full-length novel in English”.

At least for Barbara Kingsolver whose latest novel The Lacuna has won the 2010 Orange Prize for fiction by women. The prize is awarded to “the woman who, in the opinion of the judges, has written the best, eligible full-length novel in English”.

The prize website says “excellence, originality and accessibility in women’s writing from throughout the world” are the criteria and the winner receives £30,000.

The judges say they chose The Lacuna because “it is a book of breathtaking scale and shattering moments of poignancy.”

As I recall the reviews of The Lacuna were not wholeheartedly favourable with the Guardian’s reviewer Alice O’Keeffe being typical. She writes the “lack of a convincing narrator leaves The Lacuna rather rootless. While The Poisonwood Bible was equally ambitious in scope, it kept its focus small and tight… in The Lacuna, Kingsolver allows history to dictate the characters, rather than the other way around”.

Obviously the Orange Prize judges disagreed.

Like a lot of other readers, I loved The Poisonwood Bible which is set in the Congo. It is consistently up there on the “favourite reads” lists but something about the hotchpotch nature of The Lacuna and the device of gaps in knowledge and the use of notebooks turned me off.

I also doggedly tried to read Kingsolver’s last non-fiction book Animal, Vegetable, Miracle about her family trying to survive on only locally produced food and goods in rural Virginia. Books about making do under constraints I love but something about the hokey Americanism, the one-big-happy-familyness, forced me to give up before I was half way through.

I quite like the cover for The Lacuna but what does it signify? It reminded me of the cover for Margaret Atwood’s The Year of the Flood (which I didn’t like – the cover, I enjoyed the book) with its entwining flowers, leaves and vines. Perhaps these author’s names sell their books alone and any obvious representational graphic on the cover would only get in the way??

Review – A Fair Maiden

16 year old Katya Spivak and 68 year old Marcus Kidder undertake an alchemical journey in Joyce Carol Oates’ A Fair Maiden. Katya is from an impoverished, fractured gambling clan in Pine Barrens and Marcus is from an old extremely wealthy well-connected local family. Both are visiting Bayhead Harbour for the summer, like the hundreds of stinging jellyfish washed onto the Jersey shore in squalls. Katya is nannying with a new-money family that Marcus refers to as the Mayflies and Marcus is visiting his family’s old summer place from his home in New York, and perhaps his wealthy cultured trust-fund family has descended from the Mayflower.

16 year old Katya Spivak and 68 year old Marcus Kidder undertake an alchemical journey in Joyce Carol Oates’ A Fair Maiden. Katya is from an impoverished, fractured gambling clan in Pine Barrens and Marcus is from an old extremely wealthy well-connected local family. Both are visiting Bayhead Harbour for the summer, like the hundreds of stinging jellyfish washed onto the Jersey shore in squalls. Katya is nannying with a new-money family that Marcus refers to as the Mayflies and Marcus is visiting his family’s old summer place from his home in New York, and perhaps his wealthy cultured trust-fund family has descended from the Mayflower.

These two meet when Marcus recognises his soul mate in Katya and woos her with a blend of personal charm, renaissance-style talents, autocratic but well-bred manner, and the borrowed allure of family wealth and position. Katya is drawn into the liaison secure that she possesses a strong bargaining chip in her sexuality and youth.

This is the card she plays initially, but Marcus’ desire for her goes beyond elderly loneliness or sexuality, and she flounders when she finds herself longing for connection and to express her own creativity. Marcus offers her money for modelling, and wanting to do better for herself than whatever Pine Barrens offers, she agrees. Katya is flattered, wary, greedy for the money Marcus pays her and which her feckless gambling mother begs for.

JCO portrays an interesting character in Marcus with his abandoned potential: the young tenor voice, musical composition, his children books, his detailed illustrations and portraits, his beautiful and strange glass fossil flowers, his film star relationships and his apparent yearning for something beyond this and quite sure his money can buy it. His creativity has not been enough, he longs for the mystery at the heart of the rose.

Katya’s world where life’s actions are throws of the dice is already also one of intoxication and intemperance. Marcus carefully tempers her wine when she sneaks out to visit him at night and model, building her up to the ultimate planned intoxication but Katya’s cousin Roy, fresh from prison and setting up his own drug dealing business to take him beyond Pine Barrens, comes once more into Katya’s world when Marcus impatiently pushes her forward too quickly one night wanting to sketch her nude.

Roy (another word for king) and that’s how Marcus refers to himself as she flees him that night: “Katya! The offer – the King – will be waiting for you”. There is explicit textual offer here to look at this story as fairy tale, perhaps Beauty and The Beast, however the references to intemperance (in money and substance) and the attempts by both Katya and Marcus to wrest some meaning or value from life’s materials had me thinking of Alistair Crowley and the alchemical journey for the philosopher’s stone.

JCO has woven a complex and textually tight story with lots of potential markers to explore which gives it depth and makes for a very satisfying read. Although the two main characters are portrayed as fairly complex and, in Marcus ’case, with a very busy life, the story revolves not on character or plot but on the issue of our search for value and meaning, and when we cannot find it, the human drive to attempt to create it out of our actions.

Before Katya’s final act for Marcus, done for love rather than money, she feels attachment for her young charges. When Katya first went to Bayhead nannying, her mother warned her against becoming attached to stranger’s children, and indeed Katya’s mother seems totally unattached to her own children. Katya finds love for the young children she has looked after and, far more dangerously for her, the charming and somewhat pathetic Marcus Kidder. Perhaps as a result of this access to love, Katya sees herself running, leaping across the stinging jellyfish tentacles on the Jersey shore before she goes to the dying Marcus.

Review by Tania.

ABIA fiction shortlists

The Australian Book Industry Awards literary fiction shortlist is: Dog Boy Eva Hornung, Jasper Jones Craig Silvey, Lovesong Alex Miller, Ransom David Malouf, The World Beneath, Cate Kennedy. Good to see Eva Hornung on the list.

The general fiction shortlist is Heartless Tasma Walton, The Cattleman’s Daughter Rachael Treasure, The Death of Bunny Munro Nick Cave, The Five Greatest Warriers Matthew Reilly and Truth Peter Temple. Interesting to note Truth here is listed as general fiction although it’s also been shortlisted for the (literary) Miles Franklin.

The winners are announced on 30 June.

Review – Of Bees and Mist

This is a trul y strange book – compulsively readable and annoying in equal measure. The cover is a bit of a giveaway consisting as it does of the title in big art deco letters on a grey background with a few white curlicues ie we’ve got no idea how to classify this. Just above the author’s name is a small picturebook-like silhouette of a tower on a cloud with a windswept woman’s figure. The publisher is tentatively suggesting this might be a kid’s fantasy.

y strange book – compulsively readable and annoying in equal measure. The cover is a bit of a giveaway consisting as it does of the title in big art deco letters on a grey background with a few white curlicues ie we’ve got no idea how to classify this. Just above the author’s name is a small picturebook-like silhouette of a tower on a cloud with a windswept woman’s figure. The publisher is tentatively suggesting this might be a kid’s fantasy.

This could be a fantasy book except it is set in a picturebook ‘real world’, in a city that might be northern European, central European or Asian; it has elements of each. It could be in medieval times, the nineteenth century or contemporary times. The clothes don’t help. In one place the heroine, Meridia, wears a knee length dress, yet her father wears a top hat and cloak. Everyone walks – there are no horses, or cars, or trains. In the gardens there are roses and marigolds but also bougainvillea, the food is cakes and sandwiches but also ginger and garlic and noodles. If we accept this hybrid world it is only one step further to accept that there are yellow and blue mists that enfold Meridia’s father when he leaves the house, that the house is perpetually freezing no matter the heat outside, and that Meridia’s mother-in-law dominates her family with vicious attacking bees that aren’t visible to others.

In Meridia’s world there are fortune tellers, invisible friends and people who fade into their spirit beings but there’s also school, romance and marriage, housekeeping and starting up a business. This mishmash of elements would be fatally off putting if it wasn’t for the strong narrative drive and the barrage of mysteries to be resolved. Meridia’s mother-in-law is a truly horrendous character, such a narcissistic sociopath that she doesn’t really need the (supernatural) bees the author bestows on her to perpetuate her horrors. Be warned, her comeuppance is a long-time coming.

The novel has been called magic realism, but it doesn’t quite fit that description, also an adult fairytale. That tag doesn’t really fit either but is closer to the mark. There are sexual references and crudity of language that mark this out as ‘adult’ whereas the story itself could be young adult, or teen. Perhaps as the phenomenon of Harry Potter showed, adults do want to read young fantasy books, and Of Bees and Mist has tapped into this. Interestingly, however, they’ve marketed the novel as general fiction, not fantasy.

I found it unsettling: I thought Meridia a little too self-satisfied, her husband a dolt, the feud between Meridia’s parents unbelievable and the fate of many characters unfair but, bloody hell, I couldn’t stop reading until I’d bolted through to the end.